Whose school is it anyway?

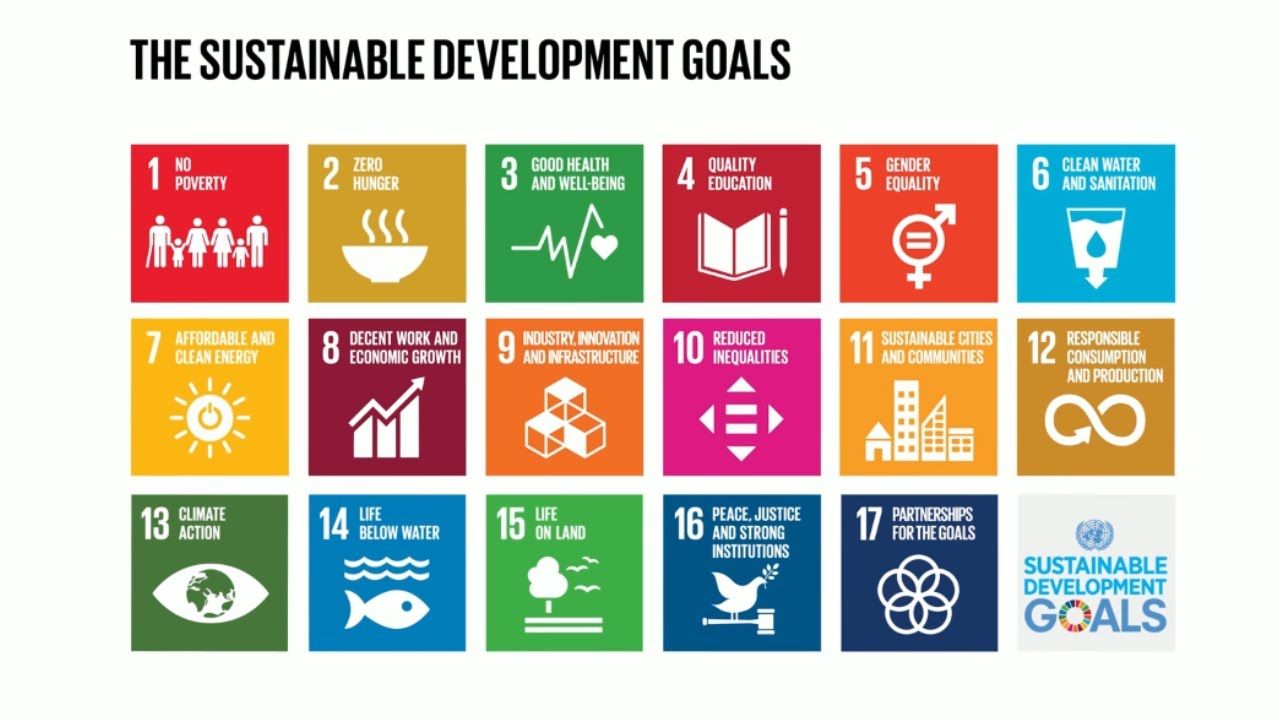

Molly Matlotlo, SDGS 4, 5 & 10 PRACTITIONER / MASTER TRAINER AT MOLTENO INSTITUTE OF LANGUAGE AND LITERACY, explores South Africa’s education, inequality and the quest for a national identity.

Every now and again, we all sit around a metaphorical table and have the same conversation world-wide. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, we were all infected and affected. We had to grapple with what it is that we’re dealing with, the implications and how we are going to get out of it. Locally, this conversation hasn’t been easy. The title for the world’s most unequal society belongs to my beloved country, South Africa. With the highest Gini Coefficient, the COVID-19 pandemic has left us exposed with education and economic disparities in full view. Catering to different socio-economic groups, their education needs and what their money can buy, we’re essentially running multiple education systems. What virtual learning could do for some, it couldn’t do for most. Where parental involvement could get some families, others couldn’t go. What books in the home could achieve for some, their absence was felt where there aren’t shelves to fill up.

The legacy of the difference in government spending on education along racial lines pre-democracy still haunts us. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 seeks to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. While spending R146 per Black learner and R1 211 per White learner, the Apartheid government was not ensuring inclusive and equitable education. With universities also not designed with Black learners in mind, the spaces are largely unaccommodating in their structures and institutional culture. Students often feel far removed from the curriculum content, which they claimed does not reflect their lived experiences, especially in the Humanities and Law. Calls for a decolonised curriculum have been prominent in recent years. Language policies have also been under scrutiny as language has been used in South Africa to grant and deny access. Although the country boasts 11 official languages, the majority of instruction at universities is conducted in English or Afrikaans. These languages are a second or even third language for most students. The insecurity that comes with teaching and learning happening in your second or third language triggers fears of intellectual inferiority and not belonging. For first-generation students who are finding their way to institutions of higher learning, these uncharted waters also mean a lack of academic support from home.

On the far end of the quintile spectrum, we find quintile four and five public schools and private schools. At this intersection we find race and class. These schools were not designed with black middle-class learners in mind who are now filling chairs at these schools. With the institutional culture dictated by White Cultural Capital, bringing one’s whole self and belonging in these spaces becomes difficult. From policies about hair to what socials look like.

With all these challenges that colour our existence, it is hard to answer President Cyril Ramaphosa’s question. “Who are we as a people? What is it that defines our national character? What is it that defines our identity? What is it that we stand for? Because the values we live by, and the principles we stand for, define us as much as what we wear, the food we eat, the languages we speak, the music we listen to, and they also make up our lives”.

As they exit formal education, we expect these young people to fill positions and take up roles in society and the economy. There’s an African proverb that goes “The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth”. Do they have reason to love and serve their country or have we failed them? With all the teacher training I’m part of at quintile one, two and three schools and friends being hired as Heads of Transformation and Diversity at private schools, there is light at the end of the tunnel. We are a colourful and resilient people, Mr. President.

First published in Engage 23.