Inspiration for your human rights artworks from Ellie Barrett

Inspiration from artist Ellie Barrett, for our global competition that platforms youth voice on human rights - The World I Want To Live In: Human Rights Education - Learning through Creating. Remember to enter by the 1st June.

Imagine a ‘sculpture’. What comes into your mind? The first thing you might think of is a huge marble figure, or solid bronze shape, or a tall form of welded metal.

For a long time, ‘sculpture’ has been something that is ‘done to’ us, rather than ‘with’ and ‘for’ us. When it appears in front of us – in the gallery, in the street – it’s monumental, towering and immovable. It’s made of materials using processes and equipment that most of us have no familiarity with and no way of accessing. Whether it’s a marble figure on horseback or a polished steel cube, ‘sculpture’ often feels like something we can’t participate in and have no cultural ownership of.

In the last 100 years, some artists have pushed against this traditional idea of what ‘sculpture’ can be and started to experiment with other materials: stuff they found in the street like old car tyres and scrap metal; stuff they found in their houses like cardboard, string and fabric; and stuff they found that connected to other processes outside of art like concrete, animal fur, fat and plants.

This shift in sculpture is important when we think about learning, empowerment and human rights. It can be easy to think about these concepts as invisible things that we can’t hold in our hands. Whilst this is partly true, it’s also the case that learning and empowerment can be influenced by things we can grasp - objects, materials or even other bodies we encounter in our daily lives. These things have a profound effect on the way we absorb, process and share information, and therefore how we view ourselves, one another and the world we live in together.

Sculpture is the perfect place for thinking about material interaction and discovering more about ourselves. Getting our hands dirty making things is a way of taking up space, gaining confidence and sharing our stories. These activities are deeply connected with learning, identity and empowerment. A key element of ensuring that sculpture is an accessible activity that all sorts of people can engage in is making sure that the materials we use are familiar and accessible to as many people as possible. Once we expand the materials we use to make sculpture, we also expand the things that sculpture can do for us.

Case Study

One of my recent projects demonstrates how salt dough (how to make it) can be a useful tool to promote accessible learning and collaborative empowerment. Personal Histories was a socially engaged sculpture project supported by the National Festival of Making, based in Blackburn UK. This project enabled me to think about accessibility, production and participation as a means of creating spaces for shared learning.

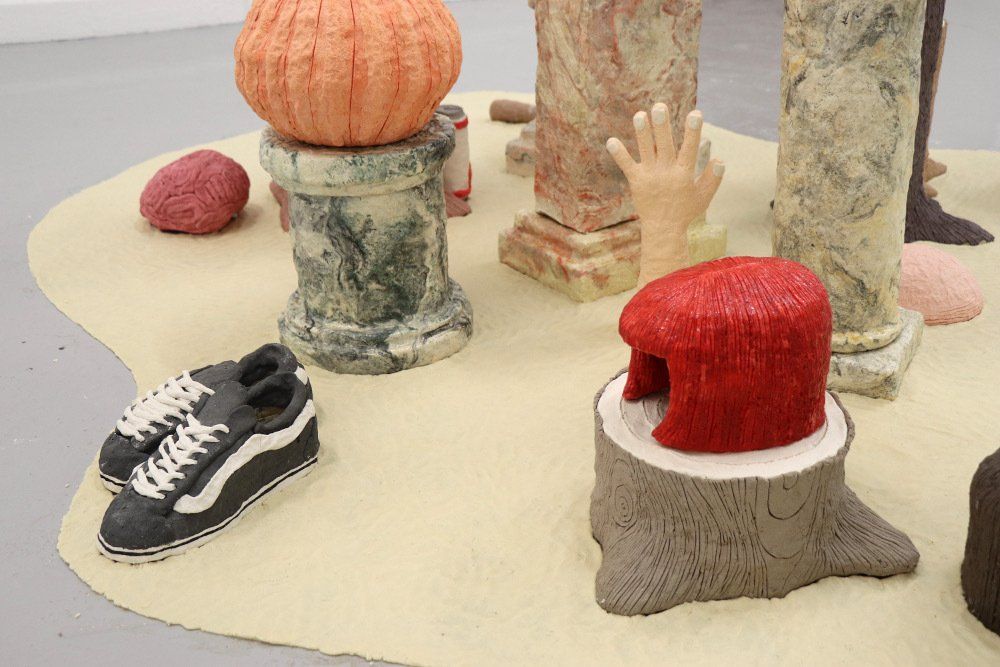

For the first phase, I researched sculpture plinths in towns across Lancashire notably in Preston, Lancaster and Blackburn. These were made from marble or stone, and most of them supported statues of powerful men. In my studio, I recreated them using only salt dough. Replicating solid, powerful structures in an everyday material is a way of removing their authority.

In the second phase, I invited people who live in Lancashire to make their own sculptures that would go on top of the plinths. I ran a series of online workshops using Zoom where we experimented with making salt dough sculpture. Material played such an important role again: these workshops were during lockdown, so we were restricted to what we could find in our homes. Salt and flour were ideal.

It was important to me that these workshops weren’t formal technical methods based, but encouraged everyone to experiment and share their discoveries. This format is called a “makerspace” and promotes non-hierarchical mutual learning from everyone in the room. I learnt a lot of new tips and tricks from the people who came to these workshops.

Afterwards, all of the participants had time to make a new sculpture using the ways of working we’d learnt from the workshops. I asked people to make something which represented their experience of the “everyday”. It was important to me that we were sharing something about ourselves using a material we have in our homes. When the sculptures were brought together, it was a way of being with each other to share our experiences, even though we weren’t able to do this in person.

The project encouraged people to think about sculpture as an accessible activity we can all use to raise our confidence levels, share our stories and learn more about each other. The completed sculptures were displayed on top of the plinths I’d made in Blackburn Bus Station in May and June, 2021.